According to Black’s Guide to Devonshire, published in 1872, “Wandsworth is the only town we know of which has two churches as ugly as those of Teignmouth”. Twenty-two years earlier, the writer of White’s Devonshire Directory of 1850 had been similarly unimpressed when he described St James’ church as “a large octagonal structure, possessing in its outward character very little attraction”. That publication was generous enough to state, however, “The interior, although of a novel and singular appearance, has some pretensions to architectural taste ...“. Such comments must have caused some indignation among the people of Teignmouth since both buildings had been erected only a few years earlier to replace the original, Norman churches.

The first church of St James was built in West Teignmouth in the late 12th or early 13th century and consecrated in 1268. Henry III was on the throne of England at that time. He was the son of King John, of Magna Carta fame, had succeeded his father in 1216, at the age of 9, and would be followed by his son, Edward I in 1272.

The old mediaeval market in West Teignmouth was held in the space where Fore Street, Exeter Street and Bitton Park Road all meet (outside where the Alice Cross Centre now stands) on 25th July each year – the feast day of St James the Great. Incidentally, the saint to whom the church was dedicated was always referred to as “St James” until 1904, when the first reference to “St James the Less” is seen. It appears first in a paper produced by Mrs M I Jordan. The reason for the change of name is unclear.

It is quite possible that St James’ was a departure point for pilgrims heading towards the shrine of St James (Sant Iago) in Spain. The Pilgrim Office at the cathedral in Santiago de Compostela have accepted a number of pilgrim trails in England as part of the pilgrimage to Santiago: St Michaels Mount (St Michaels Way) and Portsmouth (St James Way) are just two. The trail from St James’ Church, West Teignmouth, might well have been another.

Built on a rise overlooking the estuary and the marshes at the mouth of the Tame, St James’, like many churches of the time, was built for defence as well as worship. The slit windows in the tower would allow snipers with bow and arrow to pick off invaders attempting to land west of the Tame and townsfolk could withstand any assault safely inside the church. A look-out in the belfry was high enough to give sufficient warning of impending attack. This would have been particularly necessary in two incidents when Teignmouth itself was attacked and destroyed by fire, first by a French pirate, in 1340, and subsequently, on 26 July 1690, when some of the French fleet anchored in Tor Bay landed in the town and proceeded to ransack the churches, and burn 116 houses, with a number of ships and small craft lying in the harbour. On that occasion, the inhabitants had fled to safety on Haldon.

The medieval church of St James

The church was built of solid stone, covered with slate and roofed with stone. It was about 18ft high and cruciform in shape. It measured 108ft long and 24ft wide east to west. The north and south aisles, the two arms of the cross, were each 24ft long and 24ft wide. The church originally had no pillar but was later supported in the centre by a wooden pillar, the trunk of a single tree, paid for by a Mr Martyn of Lindridge and commonly known as Golden Martyn’s Pillar. There is an octagonal stone in the aisle which is believed to mark the spot where the pillar stood. Three galleries were added later, one in 1753, one in 1772 and a third in 1812. The tower, which remains to this day, is 54ft high and square from the base. It contained 4 bells, described as “of old fashioned make and of great substance and not very musical or tuneable”. Nevertheless and however tunelessly, they are said to have been rung after the battle of Crecy in 1346.

For 550 years following its construction, St James’ church continued to stand while English history was made with such events as the Black Death, the Peasant’s Revolt, the Battle of Agincourt, the Wars of the Roses, the Dissolution of the Monasteries, the Civil War, the Commonwealth and the Restoration. The Plantagenets, the Tudors and the Stuarts came and went and all of England’s churches changed from Catholic to Protestant and back again a couple of times. Then, in 1812, it was decided that the church was too small.

East and West Teignmouth were, in the early days, separate towns. West Teignmouth was a prosperous port. It sent members to a Great Council of Edward I and contributed 7 ships and 120 men to Edward III’s siege of Calais in 1347.

In 1533, Leland, a chaplain of Henry VIII, was appointed King’s Antiquary and set off on a tour of the country. He describes two towns by the name of Teignmouth. The southern of them was Teignmouth Regis, “where there is a market and a church of St Michael”. This town stood on land belonging to the King and the church was a daughter church of Dawlish. The other town, called Teignmouth Episcopi, formed part of the holding of the Bishop of Exeter. “There is the church of St Jacobi (James).”

Neither St Michael’s nor St James’ church had its own priest at this time. While St Michael’s was served by the rectors and vicars of Dawlish, St James’, as a chapel of the Bishop, was served by the rectors and vicars of Bishopsteignton.

This changed some time before 1660, when a single perpetual curate, Samuel Ware, was appointed by the vicars of Dawlish and Bishopsteignton to serve both East and West Teignmouth. The arrangement seems to have been that a morning service was held in East Teignmouth (St Michael’s) and an afternoon service in West Teignmouth (St James’) with the same congregation attending both. At that time is was common for pews or “sittings” to be purchased by those who could afford them and even passed down through families. In Teignmouth, pews were sold in either or both churches to any member of the Church of England in whatever part of the town he or she lived, the money being used for the repair of the church and any balance being given towards the poor rate of that parish.

There was great demand for these sittings and, as noted above, galleries were added at different times to increase the church’s capacity. In 1812, Sir Edward Pellew records that he paid £66 (more than £4,600 in today’s money) for three seats in the gallery of St James’ church!

Despite the arrangement for joint services, there seems to have been some animosity between the parishioners of East and West Teignmouth. A serious disagreement occurred in 1796, when East Teignmouth was becoming a fashionable watering place and its inhabitants were building houses “which are used as Lodgings a few Months in the Summer only” (it’s not just a modern phenomenon then). Believing that these houses would let more readily and for more money if they included seats in church, the churchwardens and some of the inhabitants of East Teignmouth tried to allocate to them seats which were normally used by the parishioners of West Teignmouth attending the joint services.

A further conflict arose between the two parishes when it was suggested that the service arrangement should be altered so that the morning service would be held in West Teignmouth and the afternoon service in East Teignmouth. A number of good reasons were put forward by the parishioners of West Teignmouth for the continuation of the old arrangement, the first being that West Teignmouth contained nearly 4 times the number of houses that were in East Teignmouth, 318 against 88. Among other reasons was a description of the church of West Teignmouth as being “very large and commodious” and capable of accommodating the inhabitants of both parishes much better than the East Teignmouth church, which was “a small ordinary building and not capable of containing half the number of people”.

Regardless of it’s being considered very large and commodious at that time, only a few years later St James’ church was deemed to be too small and the idea was formed of rebuilding it,

In a series of meetings between 1808 and 1811, the church trustees considered repairing, enlarging or rebuilding the church and, on 11 December 1812, an apparently surprisingly small group meeting agreed to petition Parliament to pass an Act allowing the provision of “a new and elegant edifice of larger size”. This Act was passed and received Royal Assent from George III on 19 July 1815.

The old church was pulled down in the spring of 1819.There was much discussion surrounding the state of the tower and a faculty (permission from the diocese) was obtained on 2 August 1820 to remove it but this has never been acted upon and the tower stands to this day, the oldest building in Teignmouth. One other relic of the old church remains in the new one – the 14th century carved stone altar piece or reredos. This was discarded during demolition but was purchased for £1 by the Rev Richard Lane, kept safely and later installed in the new building, Rev Lane having his £1 reimbursed.

The new St James’ church was completed in 1821. It was consecrated on 11 September 1821.

The octagonal shape of the church is unusual and, as far as I can ascertain, there are only 18 other octagonal churches within the Church of England. It was built by Andrew Patey of Exeter and is said to be his most ambitious church design. The design owes a lot to Sir Edward Pellew, who provided a good deal of the necessary funds for its construction. There is a clear Moorish influence, which is reminiscent of the buildings around Algiers, the stronghold of Omar Agha, Dey of Algiers, which Pellew bombarded in 1816 to free Christian slaves and attempt to end the practice of kidnapping and enslaving Europeans. The roof is exceptional. It is supported by a circle of eight ribbed cast-iron columns approximately 10 metres high with cast-iron rib vaults that fan out from each to form an umbrella-like structure. The central lantern has similar vaulting; eight panels below the windows each have paired hemi-spherical arched niches with trefoil heads flanked by moulded panels. This construction gives the interior a wonderfully light and airy feel.

On completion, all the exterior walls of the church and the tower were covered with rough-cast.

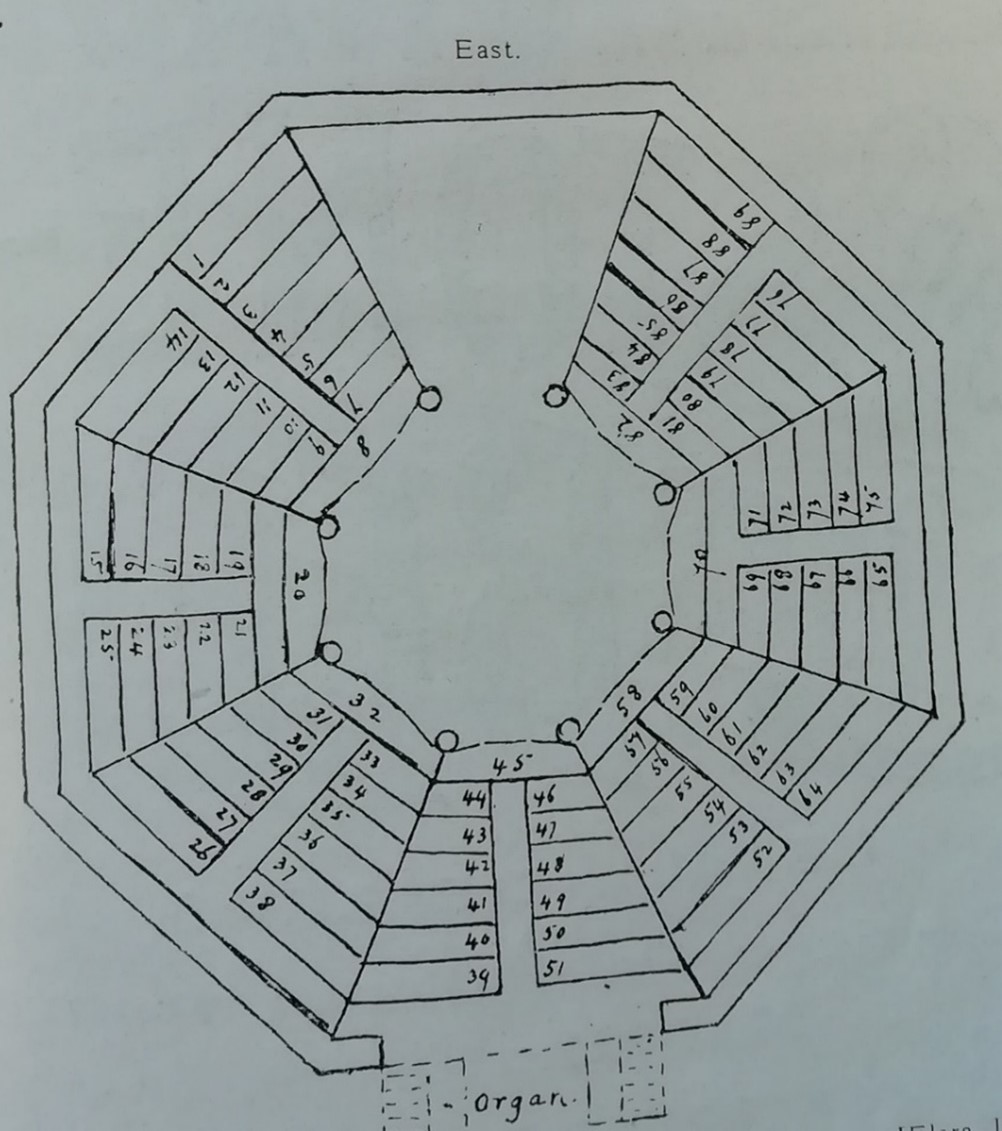

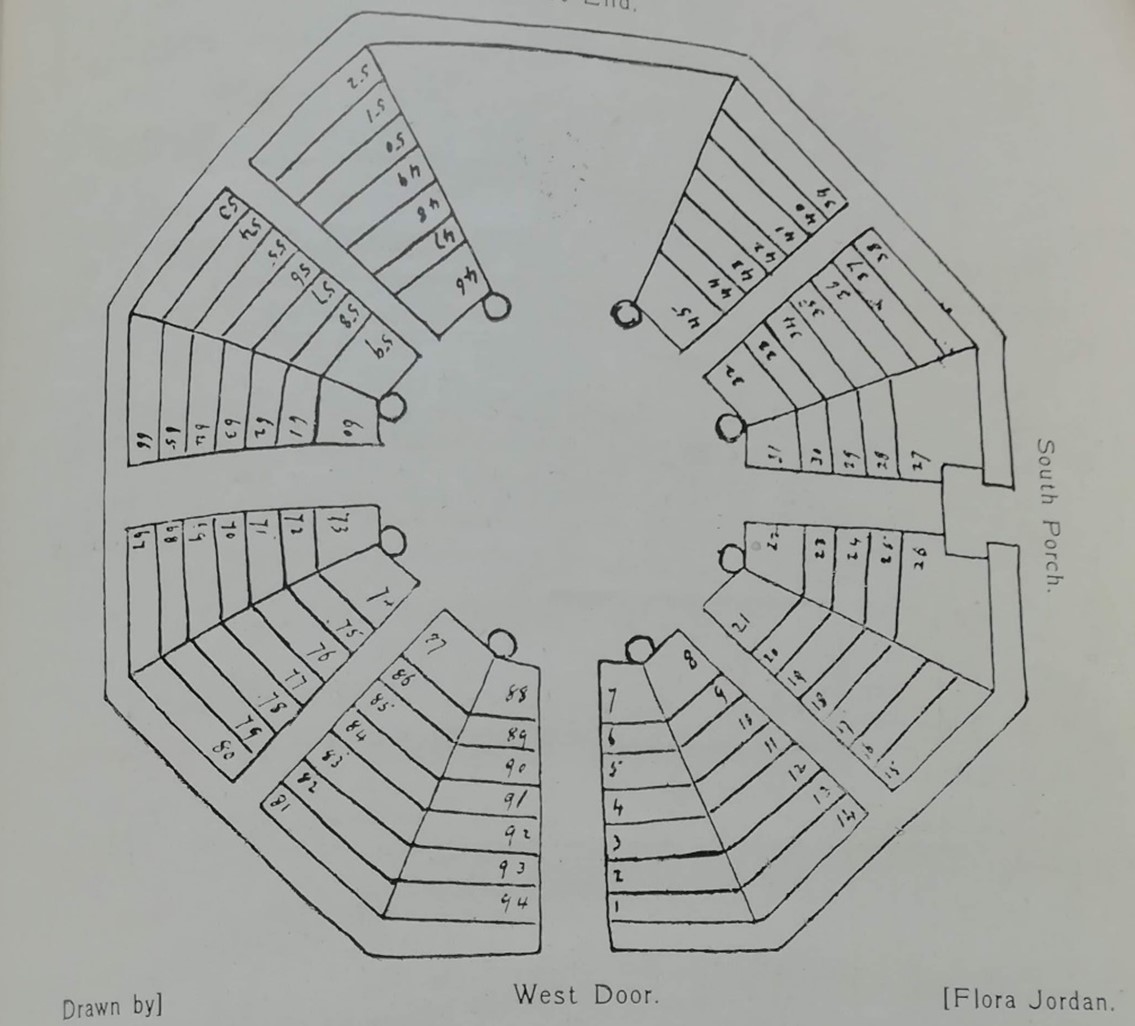

Floorplan of St James'

The church was built to accommodate a congregation of 1,500 and arranged inside were galleries to all sides of the octagon except the eastern. A good income resulted from selling those sittings! However, two of the galleries were removed in 1862 and two more were removed in 1891 when it was ascertained that they were unsafe. Another part was removed in 1920 when the Memorial Window was installed. Only one part of the gallery remains now, which houses the organ loft. You can see the organ pipes there but the gallery is no longer used

Below the galleries, the pews were arranged concentrically to follow the octagonal lines of the walls.

Seating plans at St James' church

This arrangement was changed in 1890, when the interior was remodelled to its current formation with all pews facing east. A vestry was added to the south east of the church in 1893 and, in 1898, the rough-cast was deemed to give a gloomy appearance and was removed from the walls. One has to wonder if it was a mistake to remove that protection as the walls suffer constantly today from the wet.

Unusually, the St James' war memorial takes the form of the painted North window, where the names and the regimental and naval badges of 110 members of the parish, 16 officers and 94 men, who fell in the 1914-1918 war are recorded. Each name is etched into one of the diamond shaped panes of glass. The names of the 55 men who fell in the 1939-1945 war are recorded on a panel below the window. Luckily, the church escaped serious damage from the bombs that fell nearby in Bitton Street and the surrounding area in July 1942 but fire, probably from the cannon and machine gunning that accompanied the bombing raids caused the church roof to catch alight.

St James’ church has been the centre of many people’s lives for over 850 years. It continues to be a spiritual home for its congregation and is considered the “home church” for large numbers of people, particularly those from “old Teignmouth” families.

St James' in the busy Bitton Park Road community in the 1960s